by Katarina Hayston

Being a member in the lapidary club means we are dealing with a lot of hard material, namely rocks. Their beauty lies in the eye of the beholder but most of them will get prettier the more you polish them.

But do you know whether you are holding a rock, a stone or a mineral?

I considered this on one of these self-isolation days and thought that there would be a simple explanation. Sure there is, but as usual the more you look the more answers you will find.

Let us start with “stone”. The general definition says that a Stone is piece of rock, made of hard compacted minerals, weathered to a smooth finish. Of course there are other definitions for stone, but none that apply to us here.

As we find both “rock” and “mineral” in the definition we can ignore “stone” from here on in as it is only a piece of what we are looking for.

As the definition of stone tells us that “rock” is made of “minerals” we can deduce that “minerals have to be first in order to form rocks.

The definition for mineral says that it is a solid, naturally occurring inorganic substance. Diving deeper we find that a mineral is a solid formation that occurs naturally in the earth.

Furthermore, a mineral has a unique chemical composition and is defined by its crystalline structure and shape (usually, although some do not) and it is formed naturally by geological processes (Thank you Wikipedia).

They have definitive chemical makeup as they are always made up of the same materials in nearly the same proportions.

The most common mineral structure is silicate as they contain the most common elements found in the Earth’s crust: Silicon and Oxygen. Other elements such as aluminium, magnesium and such may be present in small quantities. The most common mineral know is Quartz.

Minerals are also defined through their physical properties, which most often than not are:

- Crystal structure: see below

- Hardness: on the Mohs scale, a ten-point scale running from the softest, talc to the hardest, diamond.

- Lustre: appearance in light

- Colour

- Streak: colour of a mineral when it has been ground to a fine powder. Often tested by rubbing the specimen on an unglazed plate.

- Cleavage: how mineral splits along various planes

- Fracture: how it breaks against its natural cleavage planes

- Specific gravity: density compared with water

- Any other properties (this one is my favourite)

Now that we have covered the basics of minerals we can turn to rocks.

Our stone definition has already told us that minerals are needed to form rocks. But in order for minerals to become rocks they have to be occurring naturally, in a solid combination.

Rocks are naturally occurring and coherent aggregate of one or more minerals.

Rocks are commonly divided into three major classes according to the processes that resulted in their formation. These classes are

(1) Igneous rocks, which have solidified from molten material called magma. Example: Basalt, Granite

(2) Sedimentary rocks, those consisting of fragments derived from pre-existing rocks or of materials precipitated from solutions. Example: Sandstone, gypsum, Opal (a siliceous sedimentary rock)

(3) Metamorphic rocks, which have been derived from either igneous or sedimentary rocks under conditions that caused changes in mineralogical composition, texture, and internal structure. Example: Slate and some marbles

These three classes, in turn, are subdivided into numerous groups and types on the basis of various factors, the most important of which are chemical, mineralogical, and textural attributes. And rocks can also contain organic matter, whereas minerals do not.

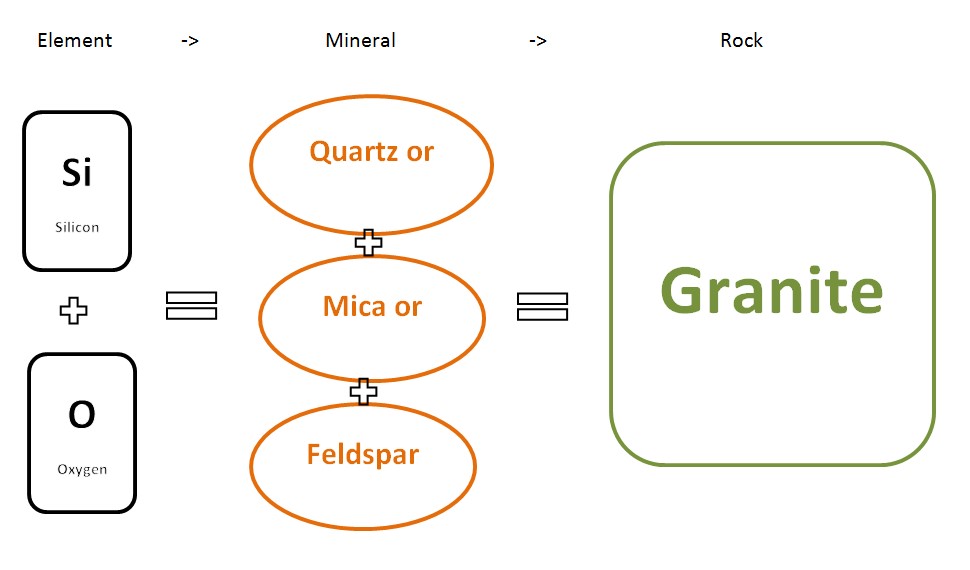

Maybe this helps to explain the mineral & rock situation:

Elements are needed to form Minerals. Depending on the quantity of each element present, the same elements may form different minerals.

One or more minerals (in this example all three minerals are needed) form rock under certain circumstances.